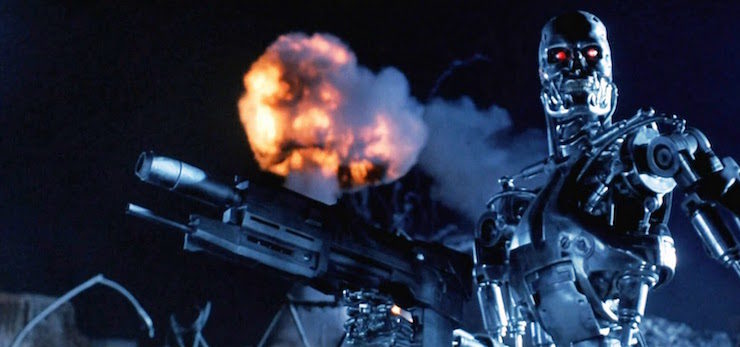

Happy belated anniversary of Judgment Day, everyone! August 29th, 1997 was the day that Skynet became self-aware and ended the world, according to 1991’s Terminator 2: Judgment Day. Or at least, it was one of several Judgment Days, depending on which timeline you follow. If there’s one thing the Terminator franchise’s refusal to die has taught us, it’s that the End of the World is a movable feast.

Judgment Day remains a high-water mark for action movies even today and it’s easy to see why. The freeway chase and Cyberdyne sequences in particular are still among the best action scenes Western cinema has ever put on the screen, and you can’t deny either Cameron’s ambition or how well it’s executed in this film. But, the excellence of its many action scenes aside, T2 as a whole has aged in a wildly variable number of ways, and some aspects hold up far, far better than others.

The element that’s held up best over the years is the cast, and perhaps not in ways you’d expect. Linda Hamilton turns in a career-best performance, and the years have only served to enhance our sense of how nuanced, brave, and deliberately unsympathetic a performance it is. After an offhand reference to just how young Sarah was in the original movie (she was 19?!), we meet her again after she’s spent a decade in the underground. Confined at the Pescadero Mental Hospital, this Sarah Connor is no one’s victim. She’s focused, driven, lean. Hamilton’s first appearance on screen is silently doing pull-ups on her overturned bed, her entire body still. It’s a stiff, mechanical series of gestures, and the film is continually at its best when exploring just how like her enemies Sarah has had to become in order to survive and prepare for the future.

Her purity of purpose is the polar opposite of Skynet’s. The insidious A.I. will do anything to kill John, her son, while Sarah will do anything to keep him alive—and that includes becoming as cold and driven as her foe. One of the movie’s best moments comes when she pulls John in for what he thinks is a hug. In reality, she’s methodically checking her son for wounds. It’s one of the times John registers as the ten-year old he’s supposed to be, desperate for his mom’s love and angry and confused when he gets yet another lecture instead of affection and reassurance.

That constant willingness to do the right thing, even if it’s the worst thing, is what drives Sarah and gives the film arguably its best scene. Her attempted assassination of Miles Bennett Dyson shows Sarah attempting to armour herself in the style of her nemesis; her shades, her combat fatigues, her methodical walk, her coldness and single-minded focus. All of it adds up to a woman who has survived incalculable trauma desperately trying to turn that trauma into a weapon. Had the film left her there, it would, for the time, have been iconic. What makes this take on Sarah seem vital even now, though, is her moment of self-realisation. Holding a gun on a badly wounded man as his family try and shield him with their bodies, Hamilton shows us everything going through Sarah’s mind: the rage, the terror, the self-loathing. It all comes crashing down, and Sarah Connor wakes up to herself. It’s an unflinching moment of emotional subtlety (all the more impressive for how little subtlety exists in the rest of the movie), and it allows her to finally close the circuit of her life. Sarah Connor, the terrified but determined 19-year-old, finally returns to Sarah Connor, the terrifying and unstoppable 29-year-old mercenary. She allows herself to become a human being, instead of an automaton unflinchingly protecting an idea, and both she and the movie are vastly improved by both her journey and that moment of self-reckoning.

Hamilton carries Terminator 2 on her back, but she isn’t always alone. Robert Patrick is the great unsung hero of the rest of the cast as the T-1000. Seeming almost impossibly young here, the heavy-set bruiser of shows like Last Resort and The Unit is instead a wiry, precise figure whose physical commitment to the role is as impressive as Hamilton’s. Pay attention to how rarely Patrick blinks; look at how he runs, and the positions he maneuvers his body into. Look at that quarter second pause he metes out during every social engagement that tells us the T-1000 is searching for the best response. It’s a measured, chilling performance that transcends the spectacular special effects that surround it. Just imagine how great it would have been if the trailers hadn’t blown the twist that he was the bad guy, not the guardian sent by the Resistance…

The rest of the cast fare much, much less well from a remove of twenty-six years. Edward Furlong gives a solid performance that’s unfortunately buried under slang that was outdated almost the moment he was filmed saying it, but there’s still a lot to enjoy. Furlong’s John Connor is at his best when he’s actually acting like a kid, his unbroken voice shrieking with terror as a truck driven by a killer machine chases him down. Better still are the moments where he shows us how John has survived the last decade. The idea of the saviour of humanity being a smug little asshole is oddly pleasing even now, and when he’s allowed to act, Furlong does a solid job. The bit where he warns Sarah that the police have arrived—she asks “How many?” and he responds “Uh, all of them, I think.”—still lands really well, too. It’s just a shame that so much of the movie sees him going full pre-apocalyptic Bart Simpson.

Schwarzenegger as an action star is, as ever, fine. Schwarzenegger as an actor is, as ever, terrible. But Schwarzenegger is almost always terrible and is at his best when he makes a virtue of that fact. The T-800 Model 101’s transition from dead-eyed Teutonic automaton to nuclear-powered father figure is one of the film’s weakest points and the 3D conversion currently showing in theaters, which from what I can tell was the original theatrical release, does it no favours. Denied the moment where his chip is switched from READ to WRITE, it casts the Model 101 Terminator as Arnie with some prosthetics on his face, quipping away even as he casually maims people. The moment where he swears, into the camera, that he won’t kill anyone was terrible twenty-six years ago and it has not improved with age. And the ending, especially in the post-Spaced world we now inhabit, is flat out laughable.

Similarly, Joe Morton had a thankless task playing Doctor Miles Exposition, and the years have show just how short-changed he was in the role. Dyson has an amazing arc: he’s a reverse Oppenheimer who rebels against ending the world, while the film steadfastly ignores him. It’s the one area of the movie that’s crying out for more detailed exploration, and Dyson offers an opportunity for a fascinating take on the franchise’s entire world. Instead, Miles is killed and his family are written out without a second look. In 1991, this was annoying. Watching now, it’s actively offensive.

Perhaps the most interesting problem with the film, viewed now, is how it’s built. T2 is Cameron on the cusp of evolving from the relentless special effects craftsman of his early work to the sprawling, Neal Stephenson-like writer of the rest of his career to date. The version I saw last week (on Judgement Day) had no READ/WRITE sequence, as mentioned above, and several of the Terminator’s social interactions, at least two of the T-1000 damage beats, the Kyle Reece cameo and the coda were also missing from the film. It still clocked in at over two hours, and that time was chopped up with (to really belabour the point) mechanical precision.

That’s often a good thing, in terms of pacing. Early scenes showing just how close the two Terminators are to locating John are a great way to ramp up tension. Likewise, Sarah’s escape unfolding as the T-1000 rolls in to kill her while John and the Model 101 swoop in to save her is almost balletic in the way the action plays out. Plus, the full-body freakout that Hamilton undergoes when Sarah sees Schwarzenegger’s Terminator again for the first time in a decade is flat-out brilliant.

But that’s all the movie does. Again and again, its pacing breaks down to “John and the T-800 go somewhere or pursue Sarah somewhere, the T-1000 attacks them, they escape, repeat.” That kind of squeezebox pacing gets predictable after a while, even with Cameron’s willingness to throw every single idea up on the screen.

It’s no accident that the most interesting character work happens during the middle act where the T-1000 temporarily disappears. It’s no slam on Patrick, whose performance is stellar, and admittedly the constant methodical pursuit element of the movie leads to some action sequences that continue to astonish even now, two and a half decades on. But that precision ultimately plays against the movie, especially on more than one viewing. The T-1000 starts to function more like an incredibly violent stagehand at times, clearing the scene and moving us to the next one, rather than an actual villain. It’s a problem that It Follows (2014) also runs into, and the two movies would make a hell of a double bill, if nothing else to see how drastically their approaches differ…

But the element of T2 that still really, truly works is simply that it successfully ends. The relics of the first movie are destroyed (although, in this cut, not the arm the T-800 loses) and the painfully written and solid future is replaced by an unusual moment of visual poetry. The image of the road, still progressing but no one knows where, provides both closure and ambiguity. No one knows where we’re going, we only know that we are moving forward, and that, in this world has to be enough. Not an idyllic happy ending, but the happiest this franchise was ever going to get, and far more successful than the flash-forward that Cameron originally scripted. In fact, Judgment Day fits so well with its predecessor that there’s a strong case to be made for them being two halves of the same finite, definitive story.

But Skynet, and the box office, never rest.

The Sarah Conner Chronicles remains an all-time great series, but not a single one of the big screen sequels that followed Judgment Day has lived up to the first two installments. Worse still, their existence turns Judgment Day into the equivalent of the relics at its heart: an aging but still innovative model being picked clean by scavengers trying to reverse engineer it. In doing so, they might get the surface elements right but ignore the consequences and emotional lessons that define this story, essentially invalidating their own efforts. That’s why they fail, regardless of the escalating scale and spectacular effects, and why, for all its innumerable faults, Judgment Day still succeeds twenty-six years later. Mostly.

Alasdair Stuart is a freelancer writer, RPG writer and podcaster. He owns Escape Artists, who publish the short fiction podcasts Escape Pod, Pseudopod, Podcastle, Cast of Wonders, and the magazine Mothership Zeta. He blogs enthusiastically about pop culture, cooking and exercise at Alasdairstuart.com, and tweets @AlasdairStuart.

I don’t remember if it was trailers or reviews or a combination of all of the above, but by the time I went to the movie, every. Single. Big. Moment. had been blown. Arnold is good! There’s a bad shapeshifting Terminator! And at one point he disguises himself as a tiled floor!, etc., etc.

Still an amazing movie, though, and groundbreaking in its use of CGI and practical effects. And when the helicopter flew under the freeway overpass, that was a real helicopter really flying under a real freeway overpass.

Too bad about all of the subsequent installments in the franchise.

I still really love this movie, for many of the reasons you mention. In fact, while I did see the third one, I don’t really accept it in my headcanon. But it’s really got some great suspense without being full on action-gore-explosion-mass collateral destruction fest like a lot of movies seem to be now. (Obviously it has all of those things but it seems to balance it well with the character moments). I know the version we have has some deleted scenes that build up more of Miles’s relationship with his family, and I think that also adds to the film.

And actually, to be honest, that last scene with Ah-nold where he tells him he knows why humans cry but that he can never do it…it kinda gets me. That and the last thumbs up.

Love this movie. Best part of the Terminator franchise.

I don’t hate the third one, though. And the “not getting a happy ending” even though it seemed like they were going to was…well, it was pretty damn interesting to me, especially the first time I watched it.

Still a big “NO” on Salvation though.

Side note, I loved the joke they made on Agents of SHIELD last season. Mack is grousing about “damn robots” and Yo-yo is agreeing:

Yo-yo: “Yes, someone should make this Radcliffe person watch all of the Terminator movies.”

Mack: “Even Salvation?”

Yo-yo: “He brought it on himself.”

I liked the film for how positive and humanistic its message was, compared to other action movies. “You can’t just kill people!” It’s shocking how few American movies acknowledge such a basic philosophy. So many movie “heroes” are killers — even ones who absolutely should not be, like Superman and Batman — that it’s deeply refreshing to me in those rare cases that they refuse to be. Sure, the whole “only kneecaps” thing was a bit hypocritical, but it was a start.

And I’m more forgiving of Schwarzenegger. He may not be a great actor, but there are things he’s pretty good at, especially comedy. And his charisma and personality carry him when his acting doesn’t. If nothing else, his larger-than-life presence made him a natural for SF/fantasy films, and there are a number of them that would never have gotten made if he hadn’t put his star power behind them, like Total Recall (which he was utterly wrong for, but which probably wouldn’t have existed without him).

And yes, in my “headcanon,” the Terminator universe consists of the first two films and The Sarah Connor Chronicles, nothing more. T3 totally undermined its predecessor. T2 ended with the declaration that there was no fate but what we make, that the future was mutable. T3 tossed that out and went back to the idea that fate was fixed and there was nothing we could do to change it (even though it changed the date of Judgment Day, contradicting itself), but it didn’t do so in order to make some kind of dark philosophical point — it was just a shallow excuse to keep the franchise going. TSCC may have done something superficially similar by establishing that Sarah had just delayed Judgment Day rather than averting it, but it also allowed for the possibility that the future could still be changed for the better, even if it was an uphill struggle. Plus TSCC actually had things to say about the future of humanity and the Singularity and the nature of consciousness and so forth, unlike T3, which was just going through the motions. As for Salvation, it was utterly awful, and I haven’t even seen the latest one because the reviews were so damning.

@@.-@ “TSCC may have done something superficially similar by establishing that Sarah had just delayed Judgment Day rather than averting it” – the show wasn’t implying that fate had any power of its own, though; the uphill struggle was because Skynet had been sending dozens of agents back in time to prop up its desired version of the future, and there was evidence that the “current” future was already different from the one the time travelers remembered.

In my headcannon There are only 2 movies and an awesome concept trailer.

I do remember I celebrated Judgement Day 20 years ago by watching the extended version.

@5/Eli: That was part of it, but another part was just the way science works — if the groundwork has been laid for a scientific breakthrough, then it will often be made by two or more groups at the same time, because it’s the natural next step. If the conditions are right for something like strong AI to be invented, then even if you stop one person from inventing it, somebody else will invent it before much longer. I think the show was heading toward the idea that the only way to win was not to prevent Skynet’s creation, because something like it would inevitably come about through some means, but rather to ensure that the strong AI that did emerge was more humane and benevolent. (Similar to Person of Interest‘s approach — there’s no stopping artificial superintelligences from emerging, so it’s just a question of making sure we end up with a benevolent AI god instead of a cruel one.)

Metatextually, though, it’s the standard approach for a time travel series in which either the protagonists or antagonists are trying to change history. It has to be at least possible for them to change it, otherwise there’s no point in even trying; but it has to be extremely difficult to make more than superficial changes, otherwise the series would end too quickly. So the general approach is to assume that history naturally tends in a certain direction due to the “flow” of events, and that whatever minor changes you make still won’t change that overall flow unless you make just the right ones at the right times. In addition to TSCC, this has been done in shows like Continuum, 12 Monkeys, Timeless, Travelers, and the first season of Legends of Tomorrow. (In that season, the protagonists were trying to undo a specific future, so it had to be hard for them — “Time wants to happen” was how they put it there. But in the second season, their job was to prevent history from being changed, so it suddenly became a lot easier to change history in order to make their job more difficult. It’s all about the rules of drama.)

Apparently James Cameron is back in control of the Terminator series, and rumor has it Arnold will play the human model for his terminators. That could be interesting. But hopefully it won’t be with a goofy southern accent like in the deleted scene from T3.

I hope we get a bit more from Skynet in the next one. Not just more action. I want to know what Skynet thinks. How does it see humanity? What would it do if all humans were exterminated? Shut down? Continue to evolve? Is Skynet a single entity? Does it ever get lonely? Does it ever feel guilt over Judgement Day? Does it feel anything?

Of course, there’s a risk of defanging the monster in answering those questions. Learning too much has a way of striping away the horror/mystery element—like with the Alien series—but a little more sci-fi, philosophical intrigue wouldn’t hurt at this point. They need a little something more besides time traveling machines throwing each other across industrial sets. Time for something fresh, maybe something smaller like with Logan.

What if Skynet (in its infinite cunning) keeps sending back Terminators to direct increasingly awful installments in the film franchise in an effort to lull us into a false sense of security?

Corny maybe, but Sarah’s “No fate but what we make” got to me. I’m a hopeless hope punk.

Watching T2’s Sarah felt like seeing a character rebelling against the plot, grabbing hold of the story and turning it in another direction. It started pretty much like a rerun of the first movie – another robot assassin, another time-travel savior, another desperate road-trip, the same iron Destiny that could only be accepted and prepared for and endured through… and Sarah chose not to play along. Insisted on treating the future as changeable, apocalypse as evadable, refused to settle for saving just one child. And she got her allies to push with her and overthrow Fate, and that’s why I can’t help wishing the series had ended there. Give me that dark hopeful road any day.

Nice shoutout for The Sarah Connor Chronicles.

Next to Hamilton, Lena Headey is a solid Sarah Connor. She certainly fits the bill more than Emilia Clarke,

I always thought that the safe bet (from Skynet’s point of view) would be not to send back yet another robot to the late 20th/early 21st century to have another go at killing a now forewarned and prepared Sarah Connor, but to send one back a bit further and try to kill, say, Sarah’s completely unsuspecting granny in 1940s California, or Sarah’s great-great-great-grandfather in late Victorian Scotland, or Sarah’s great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather in the Rhineland Palatinate during the Thirty Years’ War. That would have made quite a series.

@12/ajay: That’s basically the premise of the original movie. Skynet’s real target was John Connor, the leader of the resistance. It decided to use time travel to prevent John Connor from ever being born. But it had only fragmentary information about the prewar past. It knew that John Connor’s mother was named Sarah and lived in Los Angeles, but it didn’t know anything more specific than that. That’s why the original Terminator just tore a page out of the phone book and went around killing every Sarah Connor it could find. The “real” Sarah just got lucky that she wasn’t the first or second one on the list. So that means Skynet didn’t know anything about who her ancestors were either. John Connor was its target, and his mother was the only ancestor it had even fragmentary data on.

There was at least one Sarah Connor Chronicles episode about a Terminator sent back into the 1920s or something, but I think it was an accidental overshoot and it just tried to lay low until the right time came.

@10 – not related, but I had never heard of ‘hopepunk’ before and…OMG I LOVE IT.

I liked the voice-over in the beginning of the third, where John was totally lost as to what to do with his life after Aug 29, 1997 comes and goes without the world ending.